While there is a healthy respect between the two branches of the profession, solicitors tend to view barristers as a breed apart, as our anonymous Biglaw associate explains…

I was eager on my first morning in Court. I recognised the QC for our side in the area outside the court room. He stood there, tall and proud. His flap collar in front and ringlet tails at the back of his wig decorating the presentation of his prized noodle.

“I’m Tom,” I said, trying to catch his eye.

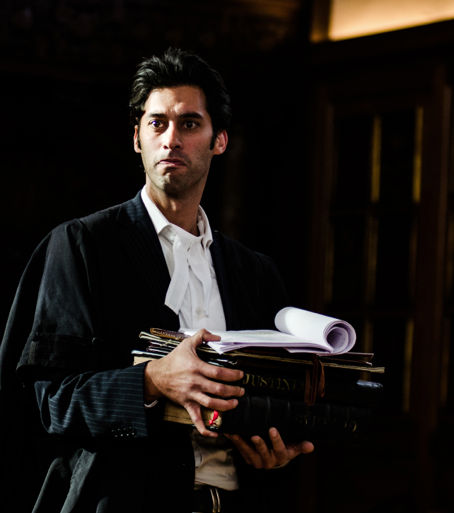

The living statue lowered his gaze. “Ah,” he said. “You’re the one who’s been clogging up my inbox”. I lowered my half-raised hand as he strode past me into the court room. Behind him, four porters hurriedly followed, zigzagging in his wake with trolleys of his documents. None appeared older than seventeen. All of them had spent a very long time on their personal presentation: tight slick side-parted hair, extra-slim white shirt, pencil tie with shiny pin. Their studied caricatures were struggling to hold themselves in place as they each carted in a sack barrow stacked high with boxes stuffed full of bundles.

They bustled around the silk, trying to anticipate his movement to lay the boxes down, building the bundles into a barricade behind his seat before he turned round, ready to pluck one of his choosing.

During court proceedings, there is an ongoing competitive dynamic between the teams of claimants and defendants. Opposite numbers sit in adjacent rows – perfect for sideways glances.

During court proceedings, there is an ongoing competitive dynamic between the teams of claimants and defendants. Opposite numbers sit in adjacent rows – perfect for sideways glances.

The QCs sit alone at the front bench atop an island of bundles and notes. Then the juniors, followed by the solicitors on another bench, then the clients and then finally the general public on the back rows. It is much like a wedding, with opponents sizing each other up across the aisle and jockeying for favour in front of the judge.

A similar reverence is seen during the recess when junior counsel, the team of solicitors and the client representatives all file into a break-out area. QC sits at the head of the table while the others sit, some stand – all ears to wait for any “pearls” from the QC as to what may happen next.

He first beckons the junior counsel, who bends down to listen. QC gives him detailed instructions on what he would like him to fetch for his lunch. The others stand in silence as he relays the type of bread, dressings, side orders and a liquid refreshment. Junior hurries out with his note in greater nervousness than I have seen him all trial.

The opposing QCs lead the theatre of proceedings: leaning on their lecterns like zealous politicians. Pulling surprised faces in mockery of their opponents’ submissions. Invoking God’s grace by turning to the ceiling or the gallery. And rising gradually onto tiptoes when making a particularly compelling point, before jabbing forward with the nose to climax. During key submissions, the other side will stifle chuckling or exchange glances.

The ultimate play is the passing of notes containing apparently crucial information. The sickly yellow post-its are scribbled on and passed from the back of the court room to the front in the vain hope that they reach the QC in time to influence his point. Each person in this legal relay takes a moment to read the note, digest it and variously raise eyebrows or nod in approval backwards to its author before passing it on.

Once, one of the notes was passed backwards. The QC winked at me as he turned. I watched it fluttering between pairs of outstretched and clasped fingers weaving through the benches on its way straight to me. What could it be? Everyone had turned their backs once again before I had a chance to open it. A one-way message, it seemed. I opened the note to reveal, first, a mobile phone number. Then in incongruously sophisticated script, the short message: “Call my wife. I will be simply unable to pick up the children from school today. JD”

I looked up to digest this instruction for a moment. QC gave me a knowing nod with solemn closure of the eyes. I stood, turned as I reached the doors, bowed ceremoniously to the judge and exited to perform my esteemed duties. The conversation that followed took a bit of explaining at first.

The proliferation of notes flickering past becomes ever more frenzied as the trial nears its end. QC whips up the room into a hurricane of hyperbole and dramatic pauses, as he disarms his opponent. Reaching him becomes all the more difficult as the scrutiny of each bench intensifies. Many notes are simply crumpled and dropped to the floor if deemed unworthy, never to be read. It is the privilege of those in front to simply turn their back without further explanation. A circle of crumpled paper builds around QC’s pulpit.

By the time the words on one triumphant note are passed into the hands of QC, it is almost too late; the performance drawing to an end. QC requests a moment from the judge while he peers over his spectacles and unfolds the crumpled note.

The inky blue handwriting bleeds into the clammy yellow paper which reads in my own outlandish writing. “Wife says: ‘you’re probably going on longer than you need to, as usual’”.

Peering behind him, QC is met with shrugging shoulders – and from the judge’s bench in front, with the most weighty of eyelids.

“Unless I can be of further assistance, those are my submissions,” QC fizzes before hurrying back to his chamber.

Tom is a solicitor at a large City firm.

Wonderful theatre!